Amongst all the skate publications, websites, catalogues or whatever it’s possible to slap photos on and jam words alongside, most writers will struggle to play cleverly with words or be inventive enough to prevent the reader from skipping the intro straight to the crux of the feature (wait, wait, there’s more). Kyle Beachy’s insights to skateboarding culture are always fascinating to come across, where he welcomes a new era of zero-budget skateboarding and encourages better reading material for those who don’t just look at the pictures. Shame he couldn’t have written this intro himself, right? Oh, you’re gone.

Interview by Stephen Cox from Issue 03 of Florecast

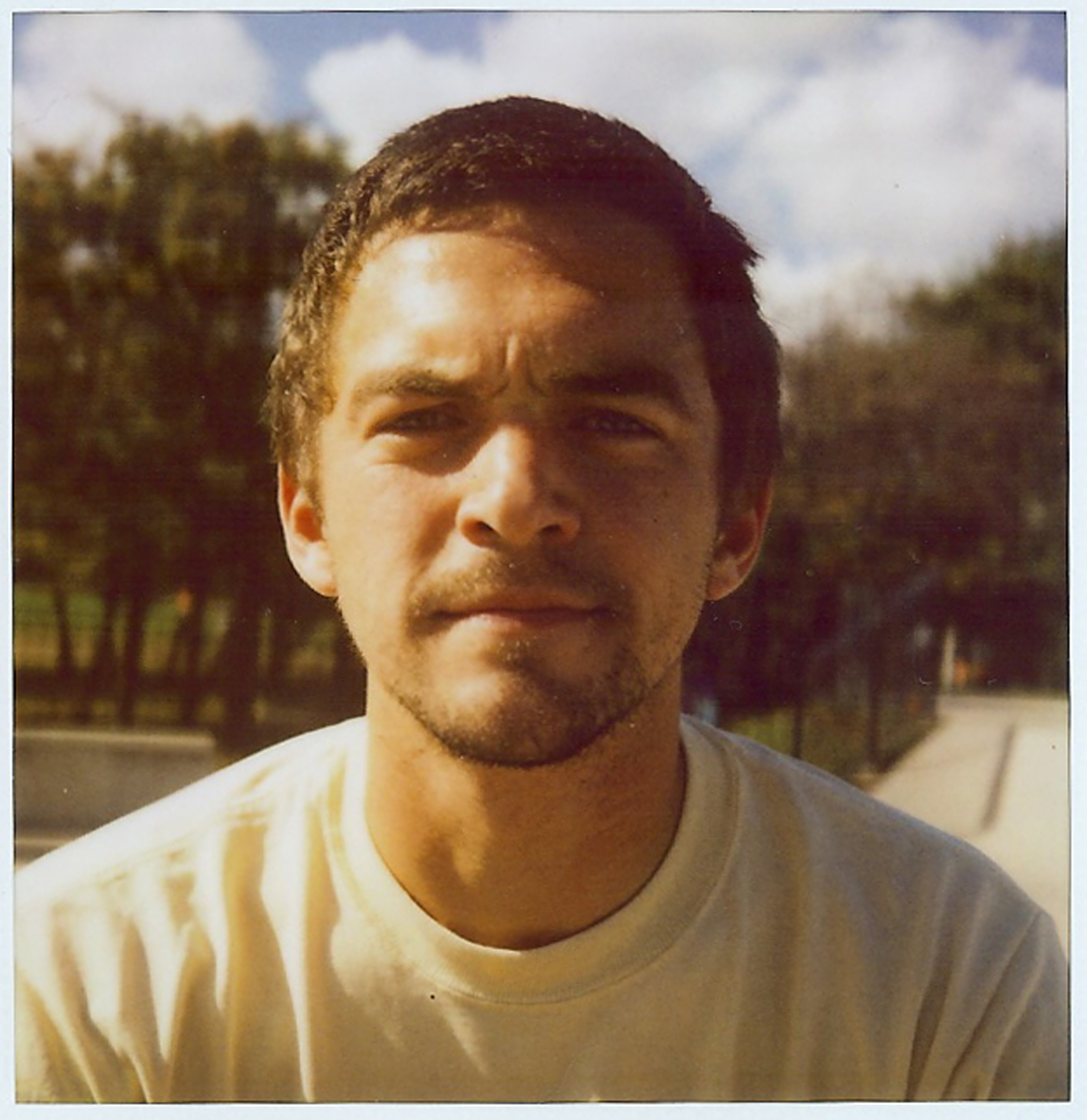

Photos by Tim Pigott and Michael Worful

Let’s start off with you. Tell our readers where you’re from and your life growing up.

I was born in Ithaca, New York, then my family moved real quickly to St. Louis, which is where I still say I’m from, despite living ten years in Chicago. My father is a plant biologist and my mother worked for Special School District and my sister was a rad badass beautiful teenage heartbreaking terror chick, and I basically scooted along quietly in her wake, generally doing well. I started skating at eleven. I skated a lot of blacktop driveways and three-stair sets.

Why do you still say you’re from St. Louis?

It’s partially about all everything that remains there, people I love and roads I can navigate blindfolded – I miss them always and feel vaguely alienated whenever I hear updates. It’s also about Chicago and its vastness, and how I meet people here who are so completely Chicago, from their accents to their innate, blood-level grasp of the city’s history, plus the way they tell stories here, there’s a whole tradition and these are people who’ve lived through so many winters and riots and murders and the rest of it that I frankly feel dishonest claiming Chicago status. Plus the Cardinals are my team until I die.

Where did you study?

I went to Pomona College, in Claremont, CA, then got an MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Pomona is a totally manicured intellectual utopia full of people, both then and surely now, who were and are much smarter than I am. SAIC is a totally bizarre creative utopia where individual expression is treated as a god and thereby given free, unrestricted range to either soar or plummet.

I understand you were encouraged to collaborate with visual artists and the like. How has this shaped your work or understanding of writing?

SAIC is very big on being genre-less, or media-fluid, or whatever we’re calling it today. I missed out on a lot of that because I was focused on The Slide during those two years of study, but Chicago is crawling with amazingly talented and weird people, some of whom I’ve met through skateboarding and some through the broader art and design world. Currently I’m doing something with Anders Nilsen, who in addition to writing these wonderful, sparse, existential comics is also stupidly good on a skateboard. Working with him is always an honour.

How did The Slide begin and how different was the outcome in comparison to your original intentions?

It began with place, this ageing, rusted midwestern city squatting sort of hopeless on its long history of expansions. I was interested in the delivery van as a kind of passport and disguise, which worked together to unfold the familiar city and reveal nooks and crannies that, for whatever reason, the main character didn’t or couldn’t see on his own. The first completed draft was radically different than what’s in print – it’s much more complete and whole now, of course, and the sentences have been run through about seven levels of revision, but also less crazy. The early drafts were batshit.

I understand that the protagonist Potter is in some way connected to you, which you found difficulty with, where achieving distance with him took time. How much of yourself and your experiences generally speaking, feature in The Slide? In what ways did you consciously try to avoid having autobiographical content?

I didn’t have to try to avoid autobiography, exactly. I developed a violent allergy and nausea for details that were my own. The split second I veered away from my true life was the moment the story became interesting, and I began to feel the freedom of actual creativity and started gradually to believe that I could maybe get somewhere worthwhile with the thing. Keep in mind that I had no idea what I was doing and that it was terrifying and disorienting and hard. And this of course is the paradox and unique beauty of fiction, that insane detour from reality that finds truth sitting there, whistling in the grass at the very end of bullshit lane.

In what ways did you structure the novel? Is it possible to have a large portion of the work done without knowing the outcome of the story?

I don’t outline, so I’ve got only a vague idea where any story will go. You hope for a kind of clearing away, right, or gradual adjustment of your eyes to the darkness of the project, so that you discover what you’re doing as you’re doing it. I’m not like César Aira, the Argentinian novelist who essentially writes a chapter or two then writes his way out of his own corners and traps, a “flight forward” as he calls it, never revising. Instead, I go for a bit then see what I have, make adjustments, go a bit more, brainstorm, draw terrible pictures, jot meaningless notes, believe whole-heartedly that I’ve “figured it out” when I sure as hell have not, plug onward, etc. You write the thing and then you write the thing, as a teacher of mine used to say. I’m a six or seven or fifteen draft writer, holding the thing to the light, scrutinizing it, always chipping away or adding more or trying to make it look right. I like to think this means I’m open to the vicissitudes or whims of creation. In practice, what it really means is that I’m an incredibly inefficient writer who’s constantly berating myself for not being more productive.

The novel won awards and had a very positive reception. I understand you were fighting demons with regards to criticism, perhaps more so than others might too. How has the reception of the book affected your creative growth and what challenges do you now face as a writer?

I was wholly and hilariously unprepared for what it meant to put a novel into the world, yes, so I could go on for a long time about the ways I’ve had to grow up since 2009. Some people liked the novel, some others did not, and most didn’t care one way or the other. So in that sense, what I felt wasn’t substantially different than what everyone goes through today when they post a picture or video, the way we count views, or page hits, or likes, or retweets, or whichever currency of support that’s at play. Book reviews and awards are no different. You realise eventually that it isn’t just lip service – you truly can not care about reviews. Which makes the answer to the last question even more important – you have to find satisfaction in the act of discovery. You have to have fun doing the thing or you’ll crumble. Good reviews do not matter. Bad reviews, unfortunately, matter more than good ones, though they categorically should not. The single greatest challenge I face as a writer is remembering that none of this stuff matters. The good news, though, is that eliminating the future noise of reception is a kind of liberation. What I’m writing now is wholly itself, whatever exactly that is. I’ve stopped worrying, mostly anyway, how it’s going to be received.

What can you tell us about the next novel? I heard you planned to incorporate skateboarding or the culture that comes with it, which I find it hard to see how this can be done in a way for those outside it to understand.

I can’t say much about the next novel except that it’s likely not going to be the ongoing thing that I’m writing about, or “about,” skateboarding. Though I’ll say that for the me the challenge of getting skateboarding to work in novel form is less about packaging it in a way that outsiders can understand it, and more about the way the activity of skating, which is essentially a non-narrative act, engages with story. The cultural world of skateboarding can serve as a fine container for a rags-to-riches narrative, or a stranger-comes-to-town narrative, and we’ve seen these deeply contrived films like Street Dreams and Hard Flip basically wrench a familiar story into the particular – and very marketable – costumes and vernacular of skateboarding. It’s just a skate version of Rad, or Airborne, or an updated Thrashin’ for the contemporary marketplace. Or you’re doing the KIDS down-and-out model of look at this subculture and its degenerates, get a load of what we call “love”. Surely there’s enough that’s innately interesting and special about skateboarding for it to create its own narrative model that breaks out of this cycle.

You’re often cited as someone who is improving the standards of what we read. What is your opinion on the current state of skateboarding literature or journalism?

That there’s anyone at all reading my writing is exciting and sort of unreal. I started doing it because I was spending a lot of time thinking about skateboarding and wanted to try and understand it – this is what “essay” means, from the French essai, to attempt. It was a trial with no real goal beyond the paired activities of thinking and writing. Skaters generally have an awkward relationship with language, and are fairly cautious with the way we deploy it. Mostly what we’re doing is labeling. We’re pointing at a photo or a video and describing it, and often making a joke. For years, what the best skateboard writing has done is embody, somehow, the spirit of the activity itself – and here I nod to Carnie, Stecyk, Cliver, and some of Nieratko’s stuff, which exudes the same vibrancy and life that we feel when we skate.

Is there anything to be said about how what we read is “dumbed down” for the reasons of potential inattentiveness in readers whilst at the same time skateboarding is largely considered as an art?

Skateboarding is a radically creative but fairly unthoughtful activity. Our culture has produced an amazing array of photographers and filmmakers and even sculptors, so it’s not a lack of work ethic or creative energy that’s stopping us from producing poets. But I don’t see it as dumbed down as much as hesitant and cautious. Look around: it’s not just that we’re unsure what skateboarding means, but we’re unsure whether it’s even a good idea to consider its meaning. Skateboarding is supposed to be fun, after all, it’s the most fun thing. Taking it too seriously can dampen or even kill this fun, so, you know, fuck it. Let’s look at the pictures. But even the meaningless, most punk reality is going to have meaning – the only question is who’s going to decide that meaning. Do we want ESPN being the leading voice in skateboard writing, reporting on contests and writing athlete profiles? Do we want VICE in charge, capitalising on our semi-subversive lifestyle and drug use? Or do we want Bobby Hundreds and other entrepreneurs hollering how we need to “start taking” and get ours? These are here, and they’re very loud. So we need more attempts, whether it’s an argument, a lyrical appreciation to the activity, a poem or story or weird, formless paragraph. A single sentence! This is the way meaning is created from within, a kind of linguistic resistance to the loud voices we can’t help but hear. Of course, it’s not every skater’s responsibility to contribute to the meaning, but the more we remain passive and detached, then we’re just children lying on our backs, suckling from a parent who knows us too well, feeding us a dream that tastes like a perfect recreation of reality.

How important is it to actively support your local skateboarding scene?

I’m not trying to prescribe what skateboarding has to be for anyone. For me, it’s most interesting when it comes out of a community like Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, or St. Louis. But for others, skating is a purely solitary activity, or a way to get laid, since, by some weird cosmic shuffle, skaters are now the cool kids in high school. The beauty of skateboarding is that there’s room for all of this plus longboards, and summer camp mega-ramps, and even those Urban Outfitters little plastic cruisers. But if you have any interest in a tapping skateboarding’s potential as a kind of axis for like-minded people to build something, or even just writing the story of a particular place in a particular moment, then it’s necessary to recognise that this means giving back. If you’re someone who takes all the time, take take take, reaping the benefits of those who go out at night to saw off skate-stoppers and bondo cracks, or the people who devote a thousand hours into filming and making videos, well, then you’re selfish.

There’s the forever ongoing debate about skater owned versus corporate. A really successful business that is skater owned can eventually get the point when the skater owned factor arguably becomes irrelevant anyway in respect of the profit involved. What are your thoughts there in terms of where the line is drawn perhaps? At what point do we stop and say this isn’t a small, independent company anymore and I need to reassess where I buy my product from?

A line! How much easier it would all be if we only had a line…but what’s so wonderful and infuriating about this question is that the second you start trying to draw a line is the second you realise that you can’t. There’s no line, no litmus for what we “should” or “shouldn’t” support. We can make broad recommendations, but ultimately it’s an ethical question that, like all ethical questions, has to be decided by the individual on a case-by-case basis. We can look to those we admire, or who have some nature of authority on the issue to elucidate things, but, again, then we have to be very, very cautious with how we’re looking, and at whom. Would we rather ask Dyrdek for guidance on finding the line, or some fastidious, nameless blogger with no insider knowledge of the issue at hand? But, now, the reason these difficult questions are wonderful is that they represent a kind of primer for young Americans and international capitalists to decide whether or not they’re going to give a shit about consumption. Caring about this stuff can potentially lead to skaters caring about larger issues – and I suppose that if there’s any guiding impulse in the things I’ve written and the stuff I want to read about skating, it’s this project of reminding us that this thing we love to do is at once totally unique and special but also, still, useful in a broader sense.

Does marketing and advertising in skateboarding often create an illusion whereby the skateboarder is under the impression they are supporting something that they are not?

I suppose so, but no more than any other commercial product does. Stamp “eco” or “green” onto a box and dull the colour palate a little and boom: new brand identity. Skateboarders are harder to trick than your average consumer, though, mainly because we believe that skateboarding is unique, and therefore exempt from a lot of the standard marketing bullshit. And this is the danger of the nostalgia that fuels a big part of our industry. Like the discussion among elders about the era when seeing someone in the street with skate shoes used to mean something. Obviously this is no longer the case, yet we remain largely distrustful of outside interests and those people who haven’t paid some kind of skaterly dues. So what we’re seeing more and more of is the model by which the small skateboarding branch of a very large, globally corporate tree has been essentially handed over to actual skateboarders. I think of this as the haz-mat model: the skater employees are like the gloves the corporation uses to handle the dangerous, fickle skate market. I do not doubt that these skater employees, these buffers between the culture and the quarterly reports, have anything but the best intentions and ideas for how to make the world rad. Still, at the end of the day, their operations are ultimately beholden to interests that do not care whatsoever about whether Peter Hewitt can pay his mortgage. And I suppose this is the interesting question, here. Will it continue to matter? In ten years, or five years, who knows, these large companies will no longer even need the homegrown marketing gestures, or perhaps even need to put on the haz-mat gloves at all, because they’ll be as natural as any other company. But of course this won’t destroy little companies, it’ll only make them more vital and necessary. Or at least one hopes.

You seem like the right guy to ask in the context of what we have discussed so far. What are you currently enjoying in the skateboarding world at the moment and where do you think things are headed?

I’m enjoying the depth and variations. Watching Suciu is the closest I’ve felt to watching Carroll in the FTC videos – it’s an actual tremble of personal excitement every time the kid appears on screen, and I watch with a child’s innocence and amazement. There’s Busenitz. Reynolds and his defiance of age. There are Dan Plunkett and Jake Johnson and Tyler Surrey and this whole tier of working class killers. The Europeans like Madars Apse and Nassim Guamaz and Gustav Tonnesen and a thousand others whose names I won’t butcher. Then the elite have their own appeal, the sparkling action figures, along with the contest spectacles that support them – it’s a kind of meta-enjoyment, but still. So, on one had we’ve got a bifurcation between the few that will be mega-rich, and the masses who will be scraping by. Like all industries, ours is seeing a collapsing of the middle class, and this will likely continue. The sparkle will continue to glimmer brightly under bigger jumbotrons and shinier lights. But our culture’s saving grace has always been its atomisation, and this will only get more radical as the financial realities continue to shift. Smaller companies, smaller overheads, more frequent and diverse video output, more genuine pride and belief in the board under your feet and what its name and graphic represent.

1 comment

Daniel Piquard says:

Mar 1, 2015

Great interview! Let’s all take off our hazmat gloves and usher in a new era of skateboard activism, you damn hippy.